Review of Functional Programming in Scala

If you’re looking to get deeper into functional programming in Scala, it’s only a matter of time before somebody mentions the appropriately named book Functional Programming in Scala, written by Paul Chiusano and Rúnar Bjarnason. It’s known affectionately as the red book, which is equally apprpriate:

The book

The book consists of 15 chapters, divided into four parts, each of which deals with some aspect of functional programming. The theory is built up very gradually.

The first part deals with functional data structures that most developers should already be familiar with, like Option, Try and List. The second part takes these structures and applies them in larger examples. This part is a little less focused and more exploring. I found it a bit harder to get through, and several other people I’ve talked to felt the same way.

It’s important to press on, though, because the real pay-off of the book, for me at least, is in part 3. Here, the authors look back on the code from parts 1 and 2 and try to discover the common patterns. This is where most of the infamous FP concepts are introduced: monoids, monads and applicatives all become clear in these chapters.

The fourth and final part deals with another infamous FP question: how do you deal with (side) effects in pure, functional code?

The exercises

Every chapter also contains exercises, which is where the true value of the book lies. Doing the exercises cemented the concepts in my brain, which helped me understand them much better.

This doesn’t mean I was able to solve every exercise myself. I often needed hints, and sometimes I would also have to look up the solution because I couldn’t figure it out on my own.

But that’s ok; that’s how you learn. Fortunately, the authors realise this, and they’ve created a comprehensive companion GitHub repository, which contains hints and answers for every individual exercise. It also contains templates for each chapter, which contain the boilerplate needed to do the exercises. Especially in the later chapters, these templates become very useful.

What I didn’t like

As I mentioned above, the second part of the book isn’t for me. The concept of this chapter was to ‘discover’ a functional library for some problem domain (for example, property-based testing and parser combinators). Inevitably, these chapters were very meandering. An approach would be explored, then discarded for a better one. While instructive, I somehow found it hard to motivate myself to doing the exercises, as I knew the results I worked so hard for could be discarded at a moment’s notice. As they authors say, this is exactly what happens in a real-world project, but it’s simply not what I’m used to seeing in a book. It could work for some people, but it didn’t work for me.

Another small gripe I have, is that the quality of the GitHub repo drops noticeably in the later chapters, especially the final one. There are virtually no hints anymore (which may or may not have been intentional), and the solutions sometimes use concepts that aren’t introduced yet. In one case, the chapter template even contains a full solution to an exercise.

I suppose it’s understandable: it’s supplementary material, and it belongs to chapters far into the book, so it makes sense if it was reviewed less thoroughly. Certainly less readers will have submitted pull requests for it. And I’m not without blame myself either, because I didn’t submit any PRs either. It did make working through the last chapter a little frustrating, though.

But these are all very, very minor issues.

What I liked

The exercises really are the best part of this book.

The pacing of the book is very good as well. Only rarely did I encounter any parts in the text that I couldn’t understand. The fact that the book starts slow and really takes the time to explain everything, is an important reason why the complex subjects later in the book don’t feel intimidating at all.

Another reason for this, is that the book is written in such a way that the practical use of every concept is made clear before the theory behind the concept is explained. You’re not studying monads for the sake of studying monads; you’re solving real-world problems for which monads happen to be a good solution. At least eight data structures are introduced and explained before it’s revealed that they’re actually monads. This way, you don’t just study a bunch of theory; you develop an intuition for what these concepts really are.

The best part

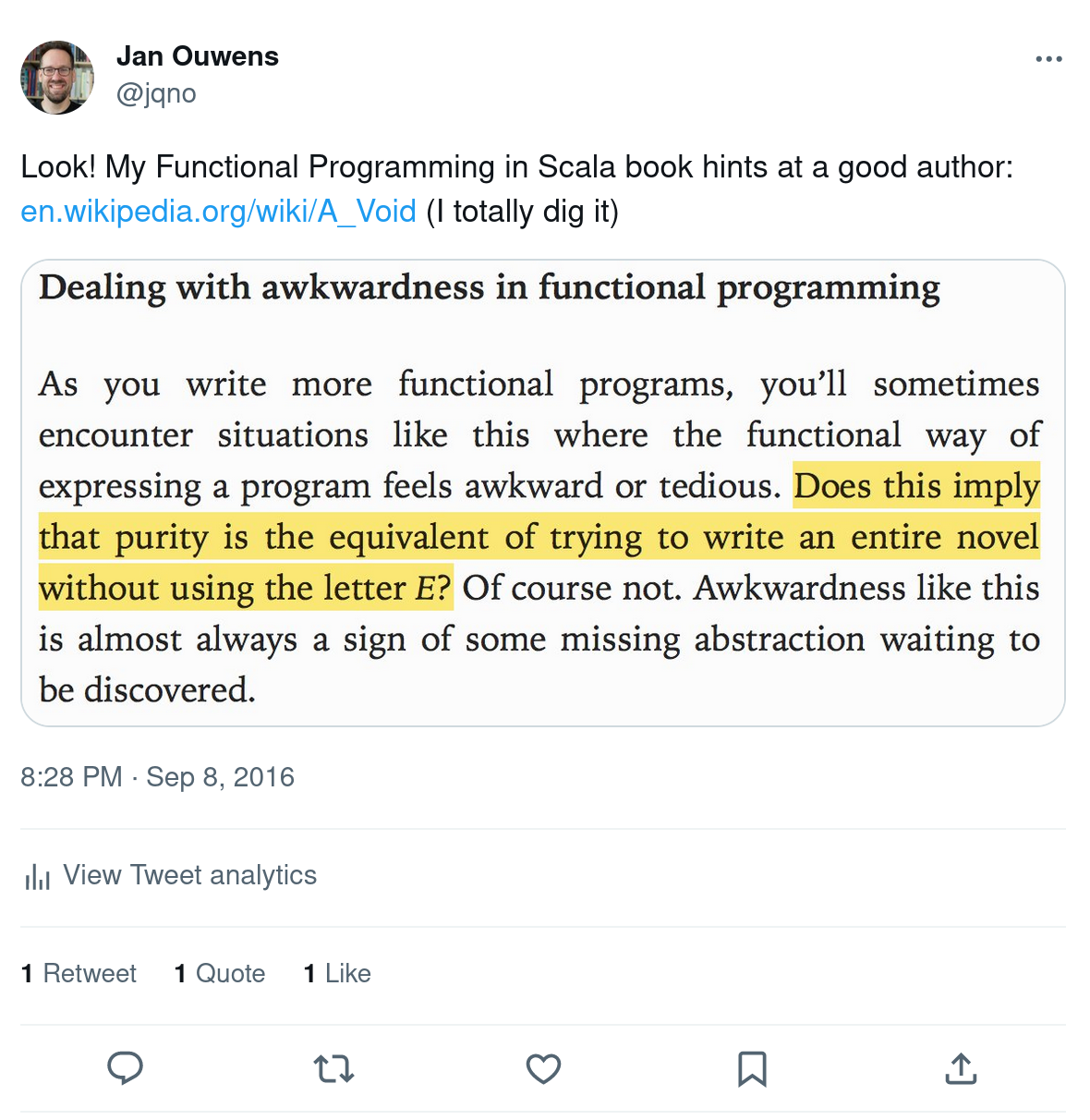

All that being said, the highlight of the book for me was actually this:

I agree with the point the authors are trying to make with that reference, but under protest, because I loved that book! (I have read the Dutch translation; it’s a real tour de force.)

Conclusion

I still can’t say that I understand every nuance of this book, but that’s nothing a second or third pass can’t solve.

The key insight for me, is that functional programming is all about how far we can take DRY. Turns out: pretty damn far. When you refactor your code in a functional way, you naturally end up with things that don’t really have an analogy in the real world. And because mathematics discovered them before programming did, they ended up with meaningless, off-putting names like monad and applicative. But in the end, these things are just design patterns and no more complex than, say, Visitor.

Does that mean I will start using category theory in the Scala code I write at work? Well, that still depends very much on the team I’m working in. I still know Java developers who struggle with lambdas, and I don’t think it’s a good idea to unleash category theory upon them immediately. But I am much more likely to start experimenting with something like Cats in my personal projects now.

I have learned a lot from this book and I highly recommend it.